Sweet: Glam Rockers and Biochemists

In 1978, a glam rock band from Great Britain called Sweet was on their way to musical obscurity. The era of musicians in sparkling tight pants, pink scarves and blaze orange platform boots was coming to an end thanks to this new thing called “Punk.” But Sweet had one last hit percolating in their minds. When they released their new single, “Love Is Like Oxygen” shot up the charts in both the US and UK.

From looking at them or paying close attention to their lyrics, you might not get the impression that Sweet were brilliant philosophers or accomplished biochemists. Nevertheless, this Love Is Like Oxygen notion of theirs has some legs. The idea that everyone needs love seems to be pretty well accepted. In child development circles especially, they seem to believe that human beings need love just to survive, much less to be happy.

But then, that’s not the kind of love I’m interested in ranting about. I was born to loving parents who would do anything for me and for whom I would do anything. I share the same sort of love with my brother, and with a small cadre of very close friends. So I’m covered on that kind of love. However, there is this other kind of love that I don’t know that I need, but certainly want. I’m going to call it romantic love. I can’t say that anyone needs it, per se. I’ve never had it, and yet I’ve managed to survive for 34 years. Nevertheless, I can say that I want it really bad, to the point that it does sometimes feel like I’ve been holding my breath for three and a half decades.

And that brings me to carbon monoxide poisoning. Every cell in your body needs oxygen to stay alive. The mitochondria in the cells require oxygen to produce ATP, which is the chemical energy source used by the cells to carry out the rest of its life processes. Oxygen is transported to each cell through your respiratory and circulatory systems. You breathe it into your lungs, where individual O2 molecules (that’s two oxygen atoms bonded together) bind with a molecule in your red blood cells called hemoglobin. These red blood cells are then pumped out to the body in your bloodstream to drop off the oxygen molecules to the rest of your cells.

The problem is that carbon monoxide (an oxygen and carbon atom bound together, or CO) can take the place of the oxygen in the red blood cell (in fact, it’s 200 times more likely to attach to a hemoglobin molecule than an oxygen molecule is, so where both are present, the CO is most likely to get the spot). So when you get a bunch of carbon monoxide in your lungs, the CO binds to the hemoglobin in your red blood cells in place of the oxygen, and is transported to your cells throughout the body. When it gets to the cells, it turns out to be useless. It can’t even be dislodged from the red blood cell, much less used to make ATP. So the more CO you breathe in, the more you increases the CO level in your bloodstream, and the less oxygen is able to get to your cells.

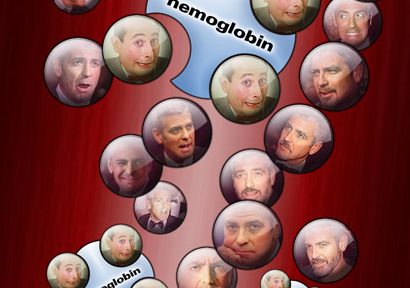

In the diagram below, George Clooney represents oxygen, and Pee Wee Herman represents carbon monoxide in the lungs. As you can see, although the Georges easily outnumber the Pee Wees, it is Pee Wee that manages to fill most all of the available link-up points on the hemoglobin molecules.

The only time Pee Wee is 200 times more likely to hook up than George

Eventually, as your cells each suffocate individually, your whole body passes out and you die. Interestingly, you don’t die in the horrible throes of pain you would might expect from being suffocated. Your body believes it is getting what it’s supposed to, as air is going into your lungs, and something is attaching to the hemoglobin in your red blood cells. So the pain that is designed to signal that something is wrong and warn you to save yourself just isn’t there. You might feel an aching in your head or some nausea to nag at you. But you can ignore that. If you do, you will drift away to a sleep from which you simply won’t wake up.

Now back to love. If love really is like oxygen, if there really is this essential emotion that we need to feel for other people and from other people, then I think there is an unfulfilling substitute for it that is just like carbon monoxide. Lust is like carbon monoxide.

Now lust is a dangerous word to use because of its connotations. I don’t tend to run into it except in religious discussions starting from a Biblical passage or perhaps a reference to the Catholic notion of the Seven Deadly Sins. Love, too, is a dangerous word, because it comes up in so many situations and has acquired so many different meanings and shades of meanings to different people. So before I go any further, I want to define what I mean by both of them.

Might as well start with love, or specifically romantic love. Romantic love, as I see it, is simply to want someone. Now that’s not precise enough, as you can want someone without being in love with them. For example, you can want your mailman because you’re expecting an important package, but you wouldn’t say you’re in love with him. So romantic love is to want someone, but for a specific purpose. I’m finding that purpose is a little difficult to nail down, probably because it’s so all-encompassing. It’s wanting someone as your lover, partner, best friend, confidante, other half…and lots of other things. So for my purposes I’m going to say that love is wanting, and romantic love is wanting a person for this all-encompassing purpose.

If you want someone a lot, that means you love them passionately. As you get to know them more and more, and continue to like and therefore want everything about them, you love them more and more profoundly. Everyone’s dream seems to be to love both passionately and profoundly, but the two are often at odds with each other. Whereas you might want a person a great deal at first, as you learn more about them, you might discover they have attributes you’re not all that keen on. So while your love might grow more profound, the passion might drop off a bit.

That’s enough on love. Lust is generally defined as strong (even inordinate) sexual desire, especially where that desire leads a person to obsessive, self-destructive, or otherwise bad behavior. I think that lust is slightly more complex than this, though, in the same way that human beings are complex. I don’t think that anyone just wants sex. I admit that we all come predisposed to instinctively want to reproduce, and there are chemicals in our body driving us to that end. But I think that we also have an innate and overwhelming desire to connect with our sexual partners at every other level as well (emotional, intellectual, spiritual…you can fill this list up with whatever you want). In other words, what we really all want is passionate, profound love. In fact, I think the reason we want sex so much is that it’s the physical manifestation of our love. When you’re having sex with someone, it feels like you are connected with them in all the other ways.

So at its core, lust is pretending to be in love. The difficulty of finding someone that you want both passionately and profoundly can motivate you to temporarily settle on a person, or even just the fantasy of a person. You pretend to be in love with them enough to feel the emotions or sexual pleasure that you would get from real love.

Now don't stare, she's just here to illustrate the point

A very simple example of lust in action is the way an average male reacts to a provocative or sexually arousing image of a beautiful woman. We look at these things, see that the woman is “hot,” and start wanting. Now we don’t know anything about her other than what she looks like, so of course our wanting is very shallow. We might start fantasizing about her, and given that we don’t know any details about her personality, we fill in the blanks with whatever we want to fit our fantasy (“wow, you love football and video games too?…that’s so awesome”). As a result, we can simulate being in love with her in our minds, and get a slight sexual buzz from it that feels like love.

Of course, if we actually did meet the model, actress, playmate, or porn star in real life, we would most likely find she had nothing in common with us. Once past her physical charms, we would most likely find very little to want about her. In fact the physical charms might turn out to be a little too artificial without all the soft lighting and air brushing. But lust is about pretending, remember. So when we’re still just looking at that picture, we pretend long enough to get whatever buzz we’re trying for, and then (hopefully) return to reality.

Can he buy you a drink?

Here’s another stereotypical example that you might not think of as an illustration of lust. A woman meets a man who outwardly appears to fulfill all her romantic desires. He’s tall, dark, handsome, has a nice car, seems socially competent and is accompanied by a group of intelligent and amicable friends. She feels immediately attracted to him, and is therefore delighted when he approaches her and asks her if he can buy her a drink. Unfortunately, before he remembers to slip it off and hide it in his pocket, she sees his wedding ring.

He manages to keep charming her, and gets her number, and they start going out on dates. She chooses to forget about the ring (which doesn’t make any more appearances) because otherwise he is so nice. This choice of hers is where she enters the realm of lust. By willfully ignoring some reality about the person upon whom she has chosen to focus her affections (and from whom she is receiving what appears to be affection), she has effectively entered a quasi-make-believe world. She likes most of the real attributes about her new boyfriend, but she decides to fantasize her way past the attributes that she doesn’t like.

Now to make our hypothetical a little more complex, perhaps at some point he comes clean, and tells her that he is indeed married, but separated. The divorce won’t be final for at least another three months. She breathes a great sigh of relief, because now she can believe that the significance of the ring she saw initially is much diminished. Perhaps the fantasy version of the man she’s been seeing is much closer to reality than that nagging little voice in her head has been saying. Where before she was forcing herself to pretend her way around that ring, now she has some evidence that allows her to believe that her pretend version of the man is in fact the real version.

But then perhaps the 3 months expire. Then 6 months. A year. He’s still married, and coming up with more an more excuses as to why. Perhaps by this point he is making the cliched promise that he will leave his wife, and he will marry the new woman. But for the woman, the reality should be coming more and more clear: he’s lying. If she chooses to be honest with herself, she will leave him. If she chooses to suspend her disbelief, maintain her fantasies, and thereby give into her lusts, she will continue to try to convince herself that the man is somehow being honest with her—that he really loves her–despite the mounting evidence to the contrary.

In both of these examples, the lust can lead to potentially poisonous results. In the second example, the negative effects are probably much more obvious. The woman wastes a great deal of her time (perhaps her prime years, her youth) on a man who will never truly love her. She can’t experience any real love during this period because her emotions are bound up in the phony relationship. Worse yet, she has to make great efforts to maintain her fantasy…she has to force herself to live a lie. When she finally has her reality check, the pain of the man’s manipulations and betrayal, the habit of being false with herself, and the self-loathing she’ll experience for convincing herself to believe in him for so long will most likely leave deep emotional scars. Her ability to trust other men will be badly diminished, and her ability to believe in love and happiness will have suffered as well. Perhaps even worse, her ability to be honest with herself will be badly atrophied.

The first example might seem more harmless. Can’t a man look at a pretty girl in a picture, have himself a quick fantasy, and go back to his life unscathed? Perhaps he can. I think he runs the risk of having his perceptions of reality warped, though, especially if the practice becomes habitual. The more he looks and lusts, the more he will focus on the value of physical attractiveness to the exclusion of other things that are much better at bringing deep and lasting happiness. To everyone’s detriment, he will contribute to the generally impossible expectations that the world has of women to look like the girls in magazines and movies. And to his own detriment, he might end up addicting himself to pornography. In the same way that hemoglobin is much more attracted to carbon monoxide than to oxygen, he might find that he has developed a greater taste for his fantasy girls than for real ones.

The more I think about it, the broader the implications of this carbon monoxide idea get. Lust doesn’t have to be sexual. You can lust for money or power or praise or whatever. Whereas generally the thinking is that lusting for anything is just wanting it to a degree that is unhealthy, I think this carbon monoxide comparison might give an idea as to how it becomes unhealthy. If you want a thing to the exclusion of some other thing that you actually need, you’re lusting after it. If you want a thing because it only feels like it fulfills a need but doesn’t really, then you’re lusting after it. If you lust for praise, maybe you really need friends. If you lust for power, maybe you really need faith. If you lust for money, maybe you really need something like…contentment. I’ll have to think about it more and cover it in another post.

For this one, I’ll just wrap it up. Love is good. Lust is bad. Love is like oxygen. Lust is like carbon monoxide. If you find that your feelings about someone are based on lies and fabrications, you’re breathing poison. If you don’t have anyone, and you’re living in fantasy, that’s poison too. So if you find yourself in any sort of romantic relationship or situation that isn’t sincere and real…well…don’t inhale.

And for those of us who are alone without anyone to love or be loved by…I guess we just have to hold our breath.

Now if you read this far in the article, here is your reward: Love is Like Oxygen, by Sweet.